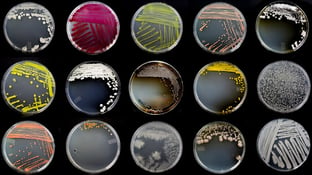

Our blog contest winner Chad Keyser is back with part 2 of his "Fear No Weevil" entry. If you missed or would like to re-read part 1, click here. I got the impression that Florence Aduto was the type of person that easily connected with people, someone you trust and want as a friend. When we asked if she wanted to participate in a research project by providing a few soil and sweetpotato samples, she was happy to help. When we returned 6 months later, she was again happy to see us, but wanted to know what we did with the last sweetpotatoes she’d given us. We explained that we were collecting samples in an effort to identify a naturally occurring microbe that could be used to control sweetpotato weevil, the most important insect pest of sweetpotatoes in Africa. I then showed her a picture of some of the microbes we had isolated so far. She considered the picture carefully, pointed to one of the Petri plates with an orange bacterial colony on it, and asked “Is this one from my yard?”.

I got the impression that Florence Aduto was the type of person that easily connected with people, someone you trust and want as a friend. When we asked if she wanted to participate in a research project by providing a few soil and sweetpotato samples, she was happy to help. When we returned 6 months later, she was again happy to see us, but wanted to know what we did with the last sweetpotatoes she’d given us. We explained that we were collecting samples in an effort to identify a naturally occurring microbe that could be used to control sweetpotato weevil, the most important insect pest of sweetpotatoes in Africa. I then showed her a picture of some of the microbes we had isolated so far. She considered the picture carefully, pointed to one of the Petri plates with an orange bacterial colony on it, and asked “Is this one from my yard?”. Microbes are everywhere, they're in the dirt, on our food, our skin, even in the air we breathe. Most are benign or beneficial to our health, a few can make us sick. Similarly, insects are constantly interacting with microbes, most have no effect, but a few are specifically evolved to be pathogenic to insects. The idea of using naturally occurring microbes to control important pests has been around for centuries, but in practice we tend to rely more on chemical insecticides than biological options. However, there are many advantages of using biological agents that make them attractive, including the potential for season-long control and low-tech production methods. The challenge is finding one that works.

Microbes are everywhere, they're in the dirt, on our food, our skin, even in the air we breathe. Most are benign or beneficial to our health, a few can make us sick. Similarly, insects are constantly interacting with microbes, most have no effect, but a few are specifically evolved to be pathogenic to insects. The idea of using naturally occurring microbes to control important pests has been around for centuries, but in practice we tend to rely more on chemical insecticides than biological options. However, there are many advantages of using biological agents that make them attractive, including the potential for season-long control and low-tech production methods. The challenge is finding one that works.

Florence’s curiosity was not unique, almost every home we visited was eager to help and interested in what we were doing. We would often find ourselves surrounded by curious neighbors and friends. Most of the communities we visited spoke their own language, in each city we would coordinate our efforts with the local town municipality and be guided from home to home by someone who could translate. Without the ability to use words to convey my gratitude, I started handing out lollipops as we were leaving. It was amazing how the simple gesture of sharing a sweet could elicit a smile and create a connection.

Each of these brief interactions left a memorable impression on me. I can still remember one woman, whose name I never learned, harvesting groundnuts when we passed her to visit a neighboring house. We said hi and she shared a handful of freshly harvested nuts with us and I in turn gave her a sucker. After we finished the collection, she followed us back to our car and asked, through the translator, if she could have another sweet because they were so good. She was so happy.

never learned, harvesting groundnuts when we passed her to visit a neighboring house. We said hi and she shared a handful of freshly harvested nuts with us and I in turn gave her a sucker. After we finished the collection, she followed us back to our car and asked, through the translator, if she could have another sweet because they were so good. She was so happy.

Over a two-year period, we collected almost 1500 environmental samples from different regions in Uganda, some in areas that experience heavy weevil infestation and others that historically don’t have any weevils. From these samples, we were able to isolate over 8,000 microbes. These are all being evaluated for their pathogenicity towards sweetpotato weevil.

As a researcher, it is easy to sometimes get lost in the science and progress we are working towards. Florence helped remind me what our work is really all about. As we were finishing up at her house, she bent over, dug around in the ground a bit with her hands, and pulled out a large sweetpotato root. After dusting it off a bit she handed it to me and said, “this one is not for research, this is for you to eat”.

.png?width=299&name=AgBiome-Logo-color-registered%20(1).png)